Home>Production & Technology>Composer>Who Is The Composer Of Gregorian Chants?

Composer

Who Is The Composer Of Gregorian Chants?

Published: December 6, 2023

Discover the composer behind the ethereal beauty of Gregorian chants. Uncover the history and genius behind these sacred musical masterpieces.

(Many of the links in this article redirect to a specific reviewed product. Your purchase of these products through affiliate links helps to generate commission for AudioLover.com, at no extra cost. Learn more)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Gregorian chants hold a significant place in the history of music. Their ethereal and captivating melodies have been enchanting listeners for centuries. But who exactly is the composer of these mesmerizing chants? The answer might surprise you.

Unlike many other forms of music, Gregorian chants were not composed by a single individual. Instead, they were the result of a collective effort by anonymous monks from various monastic communities across Europe. These monks devoted their lives to prayer, meditation, and the worship of God, and their musical creations became known as Gregorian chants.

Gregorian chants, also known as plainchants or plainsong, originated in the 9th and 10th centuries in the Catholic Church. They were primarily sung during religious ceremonies and played a vital role in creating a sacred atmosphere. The unique melodies of these chants were designed to soothe the soul and elevate the worship experience.

The development and spread of Gregorian chants were closely tied to the growth of monastic communities. Monks would gather in monasteries, living a life of solitude and devotion. It was within these monastic walls that the chants were composed, practiced, and passed down from generation to generation.

Due to the nature of monastic life, the composers of Gregorian chants intentionally remained anonymous. The focus was not on individual recognition but rather on creating a pure and harmonious musical experience that would connect the worshipper with the divine. This anonymity allows the chants to transcend time and place, making them a truly timeless form of music.

Gregorian chants flourished during the medieval period and spread throughout Europe. They were an integral part of the liturgical traditions of the Catholic Church and were sung in Latin, the universal language of the Church at the time. The use of Latin ensured that the chants could be understood and appreciated by the clergy and worshippers across different countries and regions.

Today, Gregorian chants continue to hold a special place in religious ceremonies and classical music performances. While the specific composers may remain unknown, the beauty and spiritual power of these chants endure. Their timeless melodies continue to inspire awe and reverence, allowing listeners to connect with the rich heritage of centuries of devotion and musical tradition.

Origins of Gregorian Chants

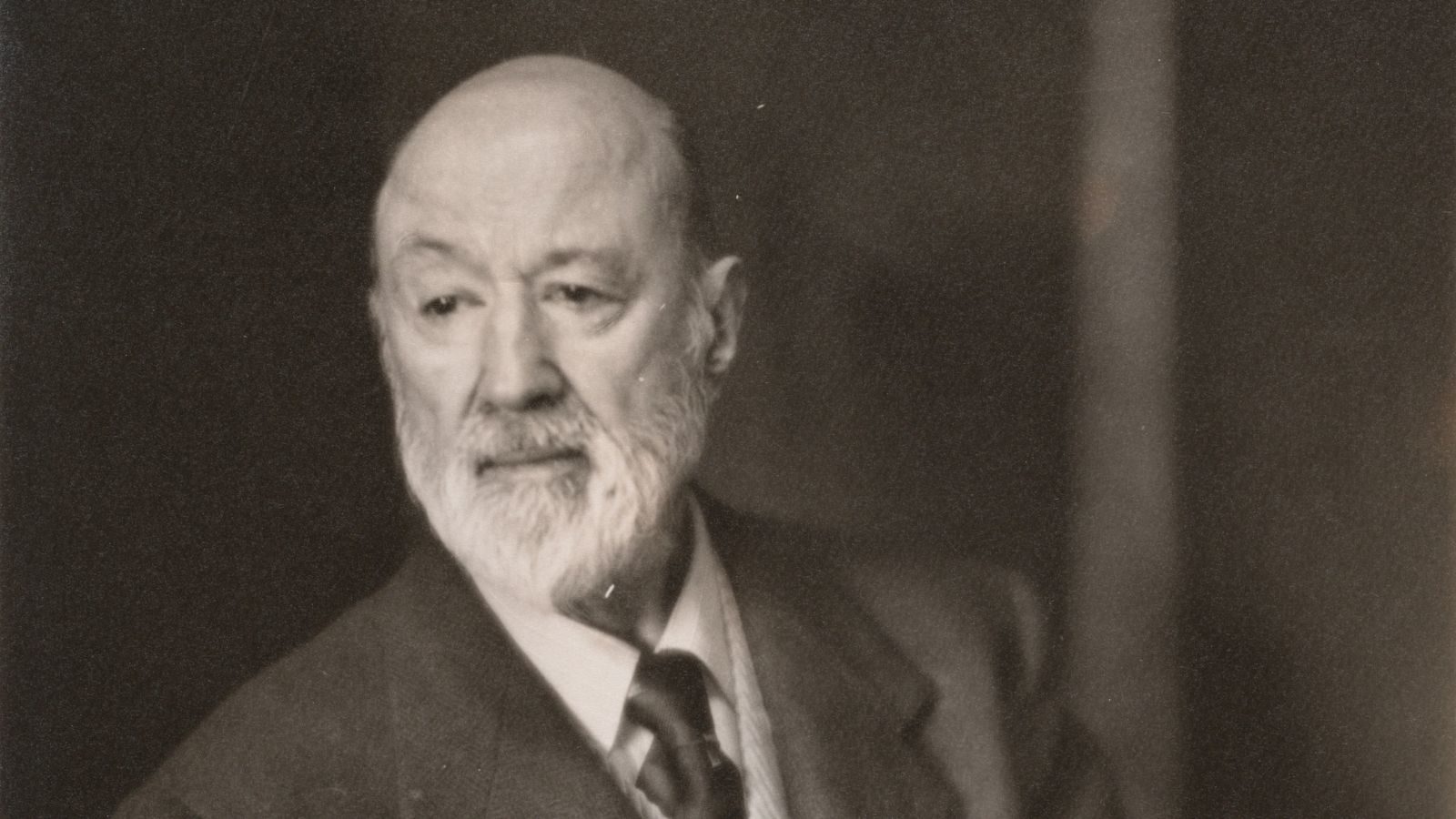

The origins of Gregorian chants can be traced back to the early medieval period, specifically to the 9th and 10th centuries in the Catholic Church. These chants are named after Pope Gregory I, also known as Gregory the Great, who played a key role in their development and standardization.

Prior to the establishment of Gregorian chants, different forms of Christian liturgical music existed. However, there was a need to unify these various musical practices to create a more standardized and harmonious sound in worship. Pope Gregory I recognized this need and took steps to collect and codify the chants that would eventually bear his name.

The collection and organization of Gregorian chants were not accomplished by a single individual but were the result of a collaborative effort by various composers and musicians within the Church. Pope Gregory I played a pivotal role in overseeing and guiding this process, ensuring that the chants adhered to certain musical principles and were suitable for liturgical use.

It is important to note that while Pope Gregory I’s contributions were significant, he did not personally compose the chants. Instead, he acted as a facilitator, overseeing the compilation and refinement of existing chants, and ensuring that they were in line with the teachings and traditions of the Church.

The sources of Gregorian chants are diverse and span across different regions and time periods. Some chants have their roots in ancient Jewish traditions, while others draw inspiration from early Christian hymns and psalms. As the chants were passed down through generations of monks and clergy, they underwent further refinement and adaptation, resulting in a rich repertoire of melodies that encompassed a wide range of styles and themes.

The development and adoption of Gregorian chants were closely tied to the monastic communities within the Catholic Church. Monasteries served as centers of religious devotion and learning, and it was within these communities that the chants were cultivated and preserved. The monastic focus on prayer, meditation, and the worship of God provided the ideal environment for the creation and refinement of this sacred music.

Over time, the popularity and influence of Gregorian chants grew beyond the monastic walls. The unique melodies and solemn beauty resonated with both clergy and laypeople, and the chants became an integral part of Catholic liturgical practices. As the chants spread geographically, different regions developed their own distinct interpretations and variations, giving rise to regional styles of Gregorian chant.

Today, the origins of Gregorian chants continue to fascinate scholars and music lovers alike. This rich musical tradition, born out of the collective efforts of composers and musicians throughout history, remains a testament to the power of music to elevate the human spirit and connect with the divine.

Development and Spread of Gregorian Chants

The development and spread of Gregorian chants coincided with the growth of monastic communities throughout Europe. These communities served as hubs of religious devotion and learning, and it was within their walls that the chants were nurtured and refined.

As monasticism gained momentum, monks dedicated themselves to a life of simplicity, prayer, and contemplation. Singing became an integral part of their daily routine, and they painstakingly developed a system of musical notation to preserve and transmit the chants accurately.

The early development of Gregorian chants was an organic and gradual process. Monks, guided by their deep spirituality and commitment to God, would compose and improvise melodies as a form of worship. Over time, these chants were collected and organized into codices, such as the famous “Graduale Romanum” and “Antiphonale Romanum,” which standardized the chants for use in liturgical settings.

By the 12th century, the popularity of Gregorian chants had spread throughout Europe. Monastic communities often served as centers of learning and cultural exchange, and monks would travel from one monastery to another, sharing and exchanging their chants. This cross-pollination of musical ideas led to the enrichment and diversification of the chants, resulting in regional variations and styles.

During the Middle Ages, the influence of Gregorian chants extended beyond the confines of monasteries and began to permeate secular music as well. Troubadours and minstrels incorporated elements of plainchant into their compositions, blending the sacred and the secular in their performances.

The spread of Gregorian chants was not limited to a particular region or language. Due to the Latin language used in the Catholic liturgy, the chants could be understood and appreciated by clergy and worshippers across different countries and regions. As a result, the chants became a unifying force, connecting people with a shared musical heritage and spiritual experience.

However, the widespread adoption of Gregorian chants also led to challenges in maintaining uniformity and preserving the authentic interpretations. To address this issue, several Church councils were convened, including the Council of Trent in the 16th century, which sought to standardize the performance and notation of the chants.

Despite the challenges, Gregorian chants persevered and continued to be a fundamental part of Catholic worship. The musical and spiritual beauty of these chants captivated listeners and inspired composers throughout history. Even as new musical forms emerged, the timeless quality of Gregorian chants ensured their enduring appeal.

Today, the influence of Gregorian chants can still be felt in various genres of music, including contemporary classical compositions, sacred choral music, and even popular music. The profound simplicity and meditative quality of these chants continue to resonate with both performers and audiences, providing a bridge between the past and the present.

The Role of Anonymous Monks

Anonymous monks played a crucial role in the creation, preservation, and transmission of Gregorian chants. These dedicated individuals, living in monastic communities, were the composers, scribes, and singers who developed and maintained the rich tradition of plainchant.

One of the primary reasons for the anonymity of the monks was the focus on communal worship rather than individual recognition. The chants were not attributed to specific composers because the emphasis was on the collective effort of the monastic community in creating a harmonious and sacred musical experience.

The monks were responsible for composing new chants, often inspired by biblical texts, Psalms, and liturgical prayers. They would spend countless hours in prayerful contemplation, seeking divine inspiration, and then give musical form to their spiritual insights. These compositions were often simple yet profound, emphasizing sacred texts and enhancing the liturgical atmosphere.

As the chants were composed, the monastic scribes would meticulously notate them using the neumatic notation system. This system, consisting of small symbols called neumes, represented the melodic contours and phrasing of the chants. The scribes’ meticulous work ensured the accurate transmission of the chants from generation to generation.

The role of the anonymous monks extended beyond composition and notation. They were also responsible for teaching and training other members of the monastic community in the performance of the chants. These musical traditions were passed down through oral tradition and practical instruction, ensuring the continued practice and preservation of this sacred music.

Additionally, the monks played a vital role in the dissemination of Gregorian chants. As they traveled from one monastery to another, whether for spiritual retreats or on official missions, they would share their chants with other communities. This exchange of musical ideas led to the enrichment and diversification of the chants, as each monastery brought its own unique interpretations and variations.

The anonymous nature of the monks allowed for a collective creative process, where the focus was on the spiritual message rather than personal accolades. This spirit of humility and devotion permeated the composition, performance, and transmission of the chants, creating a seamless connection between the earthly and the divine.

Despite the anonymity, some monks did gain recognition for their contributions to Gregorian chant. For example, Guido of Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk and music theorist, made significant advancements in the development of musical notation. His innovations helped standardize the notation system and made it easier to learn and teach the chants.

Overall, the anonymous monks were the custodians and guardians of the Gregorian chant tradition. Their dedication to spiritual reflection, musical composition, and practice ensured that these sacred melodies would endure for centuries, touching the hearts and souls of countless listeners.

Historical Context of Gregorian Chants

To understand the historical context of Gregorian chants, it is important to delve into the medieval period, a time of great religious fervor and cultural transformation. The development of these chants was deeply influenced by the societal, religious, and musical trends of the time.

Gregorian chants emerged during a period of political instability and social change in Europe. This was the time when the Roman Empire had collapsed, and new kingdoms and empires were forming. The Catholic Church, as a central and stabilizing institution, sought to assert its authority and spread its influence through religious and cultural means.

The chants themselves were intimately connected to the liturgical practices of the Catholic Church, particularly the Mass and the Divine Office. The Mass, which commemorates the Last Supper and the sacrifice of Christ, and the Divine Office, a series of daily prayers and psalmody, provided the context for which the chants were composed and performed.

During this period, Latin was the language of the Church and scholarship, making it the natural choice for the texts of the chants. The use of Latin ensured that these sacred hymns could be understood and appreciated by clergy and worshippers throughout Europe. It also became a unifying force, allowing for a shared musical tradition transcending linguistic and regional boundaries.

Gregorian chants were deeply intertwined with monasticism, a movement that emphasized solitary contemplation, asceticism, and communal worship. Monasteries played a crucial role in the preservation and development of the chants, serving as centers of religious devotion and intellectual pursuits. Monks dedicated their lives to prayer, study, and the meticulous practice of plainchant.

In addition to its spiritual significance, Gregorian chant had a practical purpose within the liturgy. Its monophonic nature, devoid of intricate harmonies or instrumental accompaniment, allowed for clarity and simplicity in worship. The prominence of the voice in these chants highlighted the importance of the sung word, merging the textual and musical elements of the liturgy.

It is also worth noting the influence of Byzantine music on the development of Gregorian chants. As the Byzantine Empire spread its cultural and political influence, Byzantine chant and notation systems had an impact on the musical practices of Western Christianity. This cross-pollination of musical ideas contributed to the rich melodic tapestry of Gregorian chant.

Over time, the popularity and widespread adoption of Gregorian chant led to the establishment of musical schools and the standardization of chant collections. Prominent centers of musical learning, such as the Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland and the Abbey of Solesmes in France, played key roles in preserving and promoting this musical tradition.

In the Renaissance and Baroque periods, as musical styles evolved, Gregorian chants faced challenges and underwent periods of neglect. However, during the 19th and 20th centuries, a renewed interest in plainchant emerged. Musicologists and composers, such as the Benedictine monks of the Solesmes Abbey, dedicated themselves to the restoration and revival of authentic Gregorian chants.

Today, the historical context of Gregorian chants reminds us of the rich cultural and religious tapestry from which they emerged. These ancient melodies serve as a bridge between the past and the present, connecting us to the spiritual heritage of centuries past and continuing to inspire and uplift listeners around the world.

Musical Characteristics of Gregorian Chants

Gregorian chants are characterized by their distinctive musical qualities, which contribute to their timeless and sacred nature. These characteristics define the essence of the chants and make them instantly recognizable.

One of the key features of Gregorian chants is monophony, meaning that they consist of a single melodic line without any accompanying harmonies. This simplicity allows the words and melodies of the chants to be heard clearly, emphasizing the importance of the text and its spiritual significance.

The melodies of Gregorian chants are often characterized by their smooth and flowing nature. They progress gently from one note to another, avoiding large leaps or abrupt changes in pitch. This melodic style, known as conjunct motion, creates a sense of tranquility and serenity.

Another notable characteristic of Gregorian chants is their use of free rhythm. Unlike more strictly metered musical forms, such as hymns or music composed for dancing, Gregorian chants are not bound by a rigid beat or meter. Instead, the rhythm is flexible and responsive to the natural inflection of the text, allowing for a more expressive and prayerful performance.

Modal scales, also known as church modes, form the basis for the melodies of Gregorian chants. These scales differ from the familiar major and minor scales of Western music. Each mode has its unique pattern of whole steps and half steps, giving the chants their distinctive melodic flavor.

The use of vocal ornamentation and melismatic passages is another hallmark of Gregorian chants. Vocal ornamentation includes various embellishments, such as trills, turns, and passing notes, which add beauty and richness to the melodies. Melismatic passages involve multiple notes sung on a single syllable, allowing for a more elaborate and expressive vocalization.

The expression and interpretation of Gregorian chants rely on the careful use of dynamic markings. While the original manuscripts did not include explicit dynamic indications, performers would rely on their understanding of the text and context to convey the appropriate dynamic nuances. This creates a sense of ebb and flow in the performance, enhancing the emotional impact of the chants.

Although plainchant is primarily sung a cappella, meaning without instrumental accompaniment, certain chants may occasionally feature a drone or simple organum. These additional tones provide a resonant background to the main melodic line, enriching the overall sound and adding depth to the chant.

Lastly, Gregorian chants possess an element of timelessness. Their melodies, unaffected by passing musical trends or cultural shifts, seem to exist beyond a specific historical period. The chants connect us to the spirituality and devotion of the past, evoking a sense of transcendence and continuity.

These musical characteristics combine to create a reverent and meditative atmosphere, inviting listeners to contemplate and connect with the divine. Gregorian chants continue to be revered for their simplicity, beauty, and profound spiritual power, inspiring awe and reverence in those who encounter them.

Notable Composers of Gregorian Chants

When discussing Gregorian chants, it is important to note that the majority of the chants were composed anonymously by the dedicated monks of various monastic communities. However, there are a few notable figures who made significant contributions to the development and preservation of this sacred musical tradition.

One such figure is Pope Gregory I, also known as Gregory the Great. While he did not personally compose the chants, he played a pivotal role in their collection and organization. Pope Gregory I recognized the need for a standardized repertoire of chants and oversaw the compilation of key melodies, which would eventually bear his name as Gregorian chants.

Another influential figure in the history of Gregorian chants is Guido of Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk and music theorist. Guido’s contributions were mainly in the field of musical notation. He developed the solmization system, using syllables such as ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la to represent different pitches. This system, known as solfege, facilitated the teaching and learning of the chants and contributed to their standardization.

Additionally, the monks of the Abbey of Solesmes in France played a significant role in the revival and restoration of authentic Gregorian chants in the 19th and 20th centuries. Led by Dom Guéranger and Dom Mocquereau, they dedicated themselves to meticulous research and transcription of medieval chant manuscripts. Their efforts led to the publication of critical editions and the establishment of the Solesmes method of chanting, which is widely followed today.

It is also worth mentioning the contributions of various chant masters and composers within specific monastic communities. For example, the monks of the Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland developed their own unique style of Gregorian chant and played a crucial role in the preservation and dissemination of plainsong in the medieval period. Their meticulous notation and preservation of manuscripts provide valuable insights into the historical development of the chants.

While the specific composers of individual chants may remain unknown, it is the collective effort of these dedicated individuals throughout history that contributed to the beauty, richness, and sacredness of the Gregorian chant repertoire. Their devotion to preserving and transmitting this musical heritage demonstrates the profound influence and enduring legacy of Gregorian chants in the realm of sacred music.

Conclusion

Gregorian chants, with their hauntingly beautiful melodies and rich spiritual significance, continue to captivate listeners across the globe. These chants, composed by anonymous monks from various monastic communities, hold a special place in the history of music and the Catholic Church.

The origins of Gregorian chants can be traced back to the medieval period, where they were cultivated within the walls of monasteries. The monks, living lives of prayer and devotion, composed and refined these chants as a means of worship and spiritual expression.

Throughout history, Gregorian chants have served as a bridge between the earthly and the divine. Their timeless melodies, marked by monophony, free rhythm, modal scales, and vocal ornamentation, transport listeners to a place of tranquility and contemplation.

While the specific composers of the chants may remain unknown, notable figures such as Pope Gregory I and Guido of Arezzo played significant roles in the collection, organization, and notation of the chants. The efforts of these individuals, as well as the dedicated monks of the Abbey of Solesmes and the Abbey of Saint Gall, have helped ensure the preservation and revival of Gregorian chants in modern times.

Today, Gregorian chants continue to be performed in religious ceremonies, classical music concerts, and recordings. Their ability to invoke a sense of reverence, reflection, and connection to the divine transcends time, language, and cultural barriers.

As we listen to the ethereal melodies of Gregorian chants, we are reminded of the profound spiritual heritage that spans centuries. These chants stand as a testament to the power of music to uplift the human spirit, providing solace, inspiration, and a glimpse of the eternal.

In a world filled with constant noise and distractions, the timeless beauty of Gregorian chants acts as a soothing balm for the soul, inviting us to pause, reflect, and find solace in the depths of sacred music.