Home>Production & Technology>Music Theory>What Is In Music Theory

Music Theory

What Is In Music Theory

Modified: February 9, 2024

Discover the fundamentals of Music Theory and unlock the secrets behind composing melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. Enhance your musical knowledge with our comprehensive guide.

(Many of the links in this article redirect to a specific reviewed product. Your purchase of these products through affiliate links helps to generate commission for AudioLover.com, at no extra cost. Learn more)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Music theory is the backbone of music. It provides a framework for understanding and analyzing the structure, elements, and patterns of music. Whether you’re a musician, composer, music producer, or just a passionate music lover, having a solid understanding of music theory can greatly enhance your musical experience.

At its core, music theory is the study of how music works. It encompasses a wide range of concepts and principles, from the basics of pitch and rhythm to complex harmonic progressions and musical forms. By delving into the realm of music theory, you unlock the secrets behind the music that moves us, allowing you to appreciate it on a deeper level.

Understanding music theory provides a toolbox of knowledge and skills that can be applied across different musical genres and styles. It allows musicians to communicate with each other through a standardized musical language, making collaboration and improvisation easier. It also empowers composers to create rich and cohesive musical compositions by leveraging the various elements and principles of music theory.

This article aims to introduce you to the fascinating world of music theory. We will explore its history, the fundamental elements of music, key concepts like pitch, melody, harmony, rhythm, and form, as well as delve into more advanced topics such as notation, key signatures, scales and modes, intervals, chords, cadences, transposition, and musical analysis.

Whether you’re a beginner looking to get started with music theory or an experienced musician seeking to deepen your understanding, this comprehensive guide will provide you with the necessary knowledge and insights to navigate the intricacies of music theory. So, let’s embark on this musical journey together and unlock the mysteries of music theory!

History of Music Theory

Music theory has a rich and diverse history that spans thousands of years. Its origins can be traced back to ancient civilizations such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, where music was deeply intertwined with religious and spiritual practices. In these early societies, the study of music focused mainly on the practical aspects of performing and composing.

It was in ancient Greece that music theory began to develop as a separate discipline. Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato recognized the mathematical and harmonic nature of music, laying the groundwork for the Western music theory that we know today. They discovered the relationship between pitch, frequency, and the mathematical ratios that govern musical intervals.

During the Middle Ages, the study of music theory was primarily carried out by monks and church musicians. Gregorian chants and sacred polyphony became the dominant forms of music during this period, and scholars like Guido d’Arezzo developed music notation systems to preserve and transmit musical knowledge.

With the Renaissance came a renewed interest in ancient Greek philosophy, philosophy, and intellectual pursuits. Music theory flourished as scholars sought to understand and codify the principles of harmony and counterpoint. Prominent theorists such as Johannes Tinctoris, Gioseffo Zarlino, and Heinrich Glarean made significant contributions to the development of music theory during this time.

The Baroque period witnessed the emergence of new musical forms, such as the fugue and the concerto. Music theory expanded to encompass concepts like tonality, modulation, and figured bass. The work of Johann Sebastian Bach is considered a pinnacle of music theory, as his compositions exemplify the intricate interplay between harmony, melody, and structure.

In the Classical era, composers like Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven further refined the principles of music theory. The sonata form, with its exposition, development, and recapitulation, became a standard structure for instrumental compositions. This period also saw the rise of music textbooks and treatises, written by composers like Jean-Philippe Rameau and Johann Gottfried Heinrich.

The Romantic era marked a departure from the strict rules of Classical music theory. Composers like Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner embraced emotional expression, expanded harmonies, and unconventional forms. Music theory ventured into new territories to explain the complex chromaticism and harmonic innovations of the time.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, music theory continued to evolve with the advent of new musical styles and technological advancements. The development of atonal and serial music challenged traditional tonal frameworks, while jazz and popular music introduced new harmonic and rhythmic concepts. Today, music theory encompasses a broad range of approaches, from traditional tonal theory to contemporary analytical techniques.

Throughout its history, music theory has served as a foundation for musical creativity and understanding. It has provided a framework for composers and performers to explore and communicate their musical ideas. By studying the history of music theory, we gain insights into the evolution of musical thought and the ways in which it has shaped our understanding of music today.

Elements of Music

Music is a complex art form that combines various elements to create an auditory experience. Understanding these fundamental elements of music is crucial in analyzing, composing, and appreciating different musical compositions. The key elements of music include pitch, melody, harmony, rhythm, form, and notation.

Pitch: Pitch refers to the perceived highness or lowness of a sound. It is determined by the frequency of sound vibrations, with higher frequencies producing higher pitches and lower frequencies producing lower pitches. Pitch is the foundation of melody and harmony, and it provides the framework for musical organization.

Melody: Melody is a sequence of musical tones that make up a recognizable musical phrase. It is the part of music that we often hum or sing along to. Melodies are a combination of pitches, rhythm, and contour. They can be simple or intricate, and they serve as the main focus of a musical piece.

Harmony: Harmony refers to the combination of simultaneous pitches in music. It involves the vertical aspect of music, where different notes are played or sung together to create chords and chord progressions. Harmony adds depth, richness, and emotional complexity to a musical composition.

Rhythm: Rhythm is the pattern of sounds and silences in music. It is the element that gives music its sense of time and movement. Rhythm is created through the arrangement of notes and rests, and it is often characterized by beats, measures, and subdivisions. It is the driving force that propels the music forward and creates a sense of groove and pulse.

Form: Form refers to the overall structure and organization of a musical composition. It encompasses how different sections of music are organized and arranged to create a coherent whole. Musical forms can vary widely, from simple binary or ternary forms to more complex structures like sonatas or symphonies. Understanding form helps us follow the narrative and structure of a piece.

Notation: Notation is the system of writing music using symbols and musical notation marks. It allows musicians to communicate and interpret music accurately. Standard music notation uses symbols such as notes, rests, clefs, and time signatures to represent pitch, rhythm, and duration. It provides a universal language for musicians to read and perform musical compositions.

By understanding and appreciating these fundamental elements of music, we can delve deeper into the intricacies and complexities of different musical compositions. Whether you’re analyzing a classical symphony, improvising in a jazz setting, or composing your own piece, a solid grasp of these elements will enhance your musical knowledge and help you communicate effectively in the realm of music.

Pitch

Pitch is a fundamental element of music that refers to the perceived highness or lowness of a sound. It is determined by the frequency of sound vibrations, with higher frequencies resulting in higher pitches and lower frequencies producing lower pitches. Pitch is crucial in establishing the melody, harmony, and overall tonal quality of a musical composition.

In music theory, pitches are represented by notes. The most commonly used system for representing pitch is the Western musical notation system, which uses a combination of letters (A, B, C, etc.) and symbols (sharp “#” or flat “b”) to indicate specific notes. The musical staff, made up of horizontal lines and spaces, is used to visually represent these pitches.

The distance between two pitches is called an interval. Intervals can be categorized as either melodic intervals, which are played or sung in succession, or harmonic intervals, which are played or sung simultaneously. Intervals are classified based on their size, such as a whole step, half step, or octave.

Pitch can also be altered through the use of accidentals, which modify the pitch of a note. The two most common accidentals are the sharp (#), which raises the pitch by a half step, and the flat (b), which lowers the pitch by a half step. Accidentals can be applied to individual notes or be used within a key signature to establish a specific tonal center.

One important aspect of pitch is its role in establishing a musical scale. A scale is a series of pitches arranged in ascending or descending order. The most well-known scale in Western music is the diatonic major scale, consisting of seven unique notes and spanning an octave. Other scales, such as the minor scale, pentatonic scale, and chromatic scale, offer different musical colors and moods.

Pitch perception is highly subjective and can be influenced by cultural and individual factors. Different cultures have developed their own musical scales and tuning systems, resulting in a rich variety of pitch relationships and tonalities across the globe. Additionally, individuals may have different levels of pitch sensitivity and pitch recognition skills.

As a musician, understanding pitch is essential for playing in tune, harmonizing with other musicians, and conveying the intended musical expression. It enables you to navigate melodies, create harmonies, and explore the intricate relationships between notes. Developing a keen ear for pitch will allow you to fine-tune your musical abilities and appreciate the beauty of melodic and harmonic structures.

Melody

Melody is a fundamental element of music that captures our attention, stirs our emotions, and allows us to sing along. It is the sequence of musical tones that form a recognizable and memorable line of music. Melodies are the heart and soul of a musical composition, carrying the main theme or idea and providing a sense of cohesion and direction.

A melody is constructed through the combination of pitches, rhythm, and contour. The pitches in a melody are the individual musical tones, while the rhythm determines the duration and placement of these tones. The contour refers to the shape or direction of the melody, whether it goes up, down, or remains stagnant.

There are various types of melodies, ranging from simple and straightforward to complex and intricate. Some melodies follow a stepwise motion, where the pitches move primarily in adjacent scale degrees, creating a smooth and flowing line. Other melodies incorporate leaps, where the pitches move by larger intervals, creating a sense of excitement or surprise.

Melodies can be composed using scales, which are sequences of pitches arranged in ascending or descending order. The diatonic major and minor scales are commonly used in Western music, but other scales, such as the pentatonic scale or the whole-tone scale, can create different melodic flavors and moods.

Repetition and variation are important techniques in creating memorable melodies. By repeating certain melodic patterns or motifs, composers can establish a sense of familiarity and provide a musical anchor for the listener. Variation adds interest and diversity to the melody by altering certain elements, such as rhythm, pitch, or contour, while retaining recognizable elements.

In addition to the pitches, rhythm, and contour, the emotional qualities expressed in a melody are essential. A melody can convey a wide range of emotions, from joy and excitement to sadness and introspection. Through the careful manipulation of melodic elements, composers can evoke specific feelings and engage the listener on a deeper emotional level.

When performing or composing a melody, musicians must consider factors such as phrasing, dynamics, and articulation. Phrasing involves dividing the melody into smaller musical phrases, allowing for breathing or resting points and shaping the overall structure of the melody. Dynamics refer to the varying levels of volume, emphasizing certain notes or passages to create tension and release. Articulation involves the specific manner in which the notes are played or sung, such as legato (smooth and connected) or staccato (short and detached).

Whether in classical, pop, jazz, or any other genre, melodies are the essence of music. They resonate with our emotions, connect us to the story being told, and leave a lasting impression. As musicians and listeners, embracing the power of melody allows us to experience the beauty and impact of music on a profound level.

Harmony

Harmony is an essential element of music that adds depth, richness, and complexity to a composition. It refers to the simultaneous combination of two or more pitches, creating chords and chord progressions that support and complement the melody. Harmony plays a crucial role in establishing the tonal quality, emotional impact, and overall structure of a piece of music.

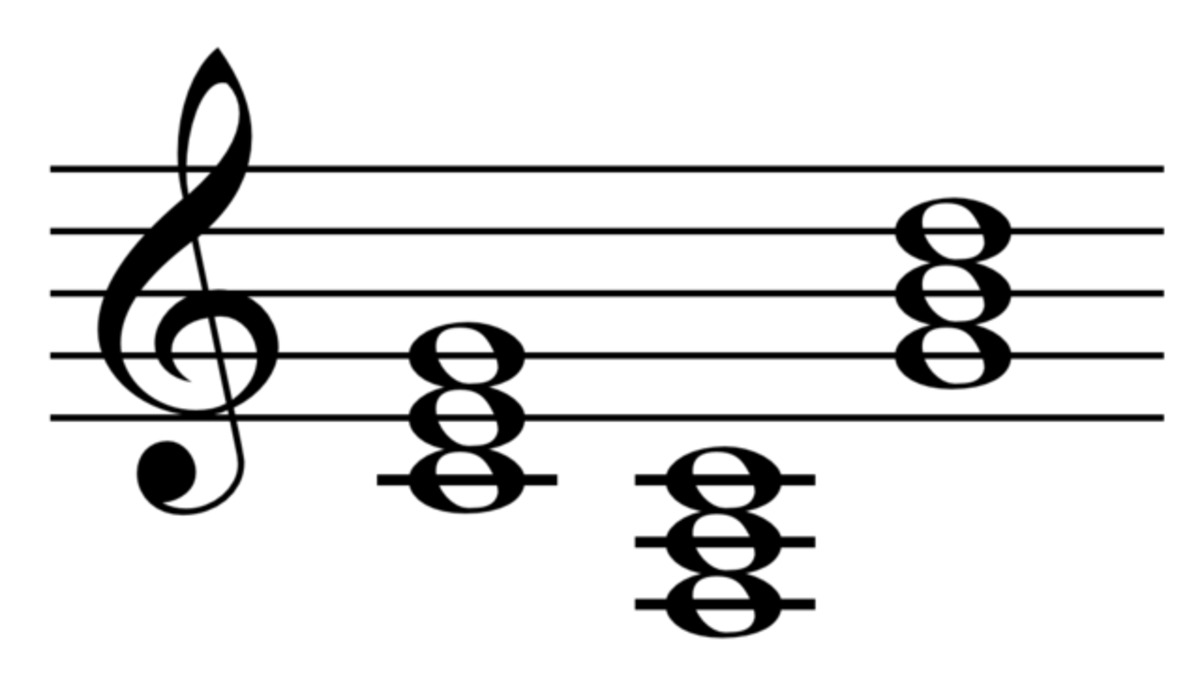

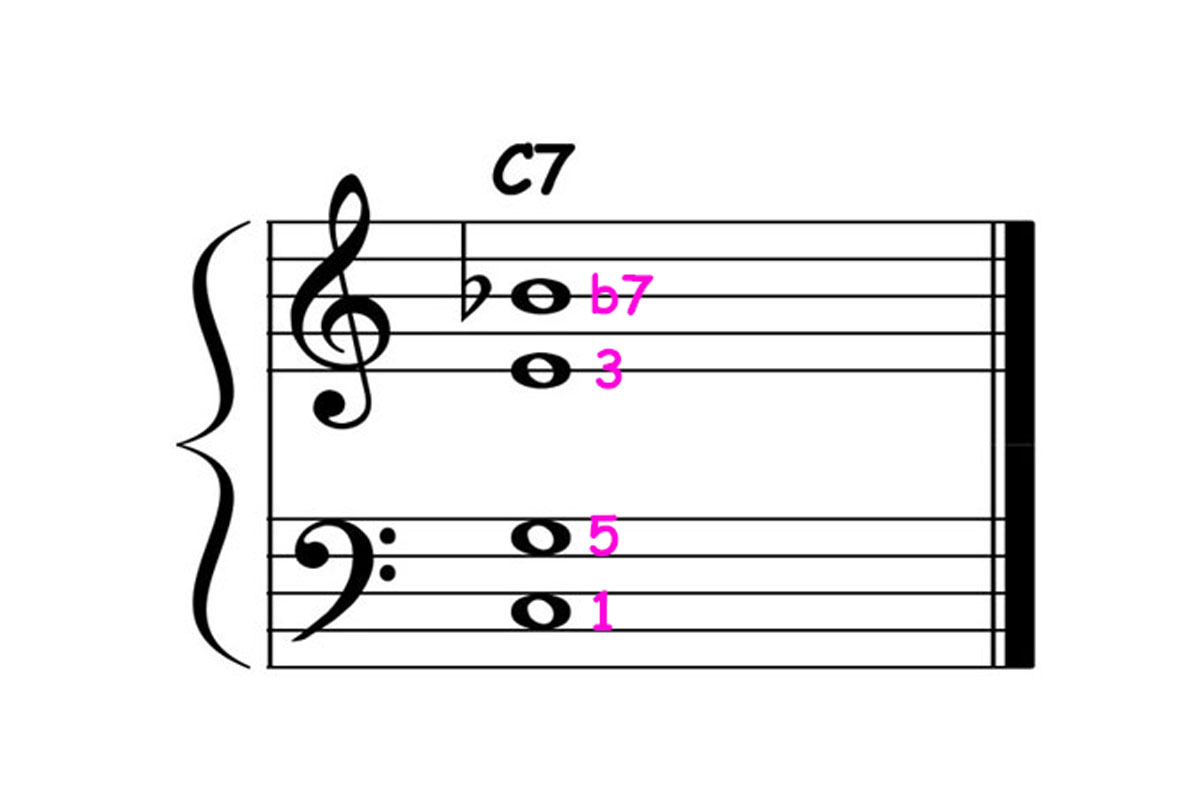

Chords are the building blocks of harmony. They are formed by stacking multiple pitches vertically, typically consisting of three or more notes played or sung together. The most basic chord is the triad, which consists of a root, a third, and a fifth. Triads can be major, minor, diminished, or augmented, depending on the quality of each interval.

Chord progressions are sequences of chords that form the harmonic framework of a musical composition. They are used to create tension and release, establish a tonal center, and guide the listener through different sections of the music. Common chord progressions, such as the I-IV-V progression in the major key or the ii-V-I progression in jazz, provide a familiar and satisfying foundation.

Harmonic function refers to the role that a chord or a series of chords plays within a key or tonal structure. The three primary functions are tonic (providing a sense of stability and resolution), subdominant (creating a feeling of anticipation or departure from the tonic), and dominant (creating tension and an inclination to resolve back to the tonic).

Harmonization is the process of adding chords to a melody or a given sequence of notes. By harmonizing a melody, composers can enrich and enhance its emotional impact. Harmonization can be achieved through chordal accompaniment, counterpoint, or more complex harmonic techniques such as modulation or chromatic harmonies.

Harmonic analysis involves identifying and interpreting the harmonic elements of a piece of music. It explores how individual chords and chord progressions contribute to the overall structure and meaning of the composition. Harmonic analysis helps musicians and theorists understand the underlying principles and choices made by the composer.

Harmony is not restricted to Western music theory. Different cultures and musical traditions have developed their own harmonic systems and tonalities. For example, Indian classical music utilizes ragas, which are melodic frameworks with specific rules regarding pitch selection, ornamentation, and rhythmic patterns. Jazz harmony includes extended chords, modal interchange, and sophisticated improvisation techniques.

Whether it’s the lush harmonies of a choral piece, the intricate voicings of a jazz composition, or the power chords of a rock song, harmony plays a pivotal role in shaping the emotional impact and overall aesthetic of music. By understanding and exploring the principles of harmony, musicians can create more engaging and compelling musical experiences.

Rhythm

Rhythm is a vital element of music that provides structure, movement, and a sense of time. It is the pattern of sounds and silences in music, created through the arrangement of notes, rests, beats, and accents. Rhythm is the driving force that propels the music forward and engages the listener both physically and emotionally.

At its core, rhythm is all about timing. It involves the organization of musical events into recurring units called measures or bars, typically indicated by vertical lines on the musical staff. Within each measure, a specific number of beats are assigned, creating a regular and predictable pulse.

Beats serve as the foundational unit of rhythm. They provide a steady and consistent reference point for performers and listeners to feel and move to the music. The speed or pace at which the beats occur is known as tempo, which can range from slow and relaxed (adagio) to fast and lively (presto).

Rhythmic patterns are created through the arrangement of notes and rests. Notes represent the duration of sound, while rests indicate periods of silence. Different note values, such as whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, and eighth notes, determine the length of each sound or silence. The combination and sequencing of these notes and rests give rise to distinct rhythmic patterns.

Syncopation is a prominent rhythmic technique that involves accentuating offbeat notes or placing accents in unexpected positions. It adds a level of syncopated or “off the beat” feel to the music, creating tension and a sense of rhythmic complexity. Syncopation is commonly found in genres like jazz, funk, and Latin music.

Polyrhythm is another rhythmic concept where multiple independent rhythms are played simultaneously. It creates intricate and layered rhythmic textures, often found in African, Afro-Caribbean, and contemporary classical music. Polyrhythms can create a sense of complexity, interplay, and rhythmic tension within a piece.

Rhythm extends beyond just the placement of notes and rests. It also encompasses the articulation and dynamics with which the notes are played or sung. Articulation refers to the manner in which the notes are performed, such as legato (smooth and connected) or staccato (short and detached). Dynamics refer to the varying levels of volume, adding expressive elements to the rhythmic patterns.

Rhythm is a universal element of music, transcending cultural and geographical boundaries. Different musical traditions have their own rhythmic systems, meters, and rhythmic patterns. The study of rhythm and rhythmic patterns plays a crucial role in various musical genres, including classical, jazz, rock, hip-hop, and world music.

Understanding and mastering rhythm is essential for musicians, as it allows for coordinated and synchronized performances. It enables musicians to play in time, follow the groove, and maintain a cohesive ensemble. It also provides opportunities for creative interpretation, improvisation, and rhythmic expression, allowing musicians to infuse their unique style into the music.

Ultimately, rhythm brings music to life and connects people through its infectious energy and compelling drive. It is the heartbeat of music, keeping it alive and moving forward.

Form

In music, form refers to the overall structure and organization of a musical composition. It provides a framework that shapes the progression of musical ideas, creating a sense of coherence, unity, and narrative. The concept of form encompasses how different sections of music are arranged and how they relate to each other.

Forms can vary widely, from simple structures in folk songs to complex architectural designs in symphonies. Some common musical forms include binary form, ternary form, rondo form, sonata form, and theme and variations. Each form has its own unique characteristics and guidelines, dictating the arrangement and development of musical material.

Binary form consists of two distinct sections, often labeled as “A” and “B.” These sections can contrast with each other in terms of melody, rhythm, or key. Ternary form, on the other hand, consists of three sections, with the middle section often providing contrast to the outer sections.

Rondo form features a recurring theme, called the refrain or “A” section, interspersed with contrasting sections. The structure is typically presented as ABACA or ABACABA, with the “A” section serving as the anchor throughout the piece.

Sonata form, commonly used in classical music, is a more complex and expansive form. It typically consists of three main sections: the exposition, development, and recapitulation. The exposition introduces the main themes, the development section explores and develops these themes, and the recapitulation restates them, often with variations.

Theme and variations form involves presenting a main theme and then altering or embellishing it through a series of variations. Each variation offers a different treatment of the theme, showcasing various melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic modifications while retaining recognizable elements.

Form serves as a guide for both composers and listeners. It helps composers organize their musical ideas, balance contrasting elements, and create a cohesive structure. For listeners, understanding the form allows for a deeper engagement with the music. It enables them to anticipate recurring themes, follow the development of musical ideas, and appreciate the overall architecture of the composition.

Within a specific form, composers have the freedom to experiment and to deviate from established norms. They can play with the expectations of the listener, introducing surprises, and creating tension and release. These deviations can enhance the expressive power of the music and provide moments of emotional impact.

Form is not limited to individual pieces of music. It can also be found on a larger scale, such as in multi-movement compositions like symphonies, operas, or concept albums. These larger-scale forms often explore different relationships and connections between the individual movements or sections, creating a coherent and unified whole.

By understanding and appreciating the form, musicians and listeners alike gain insights into the structure and narrative of a musical composition. It allows for a deeper appreciation of the compositional choices, the development of musical themes, and the overall journey that the music takes us on.

Notation

Notation is the system of writing music using symbols and marks to represent pitch, rhythm, articulation, dynamics, and other musical elements. It provides a standardized way for musicians to communicate and interpret musical compositions. Musical notation allows for the preservation, dissemination, and study of music across time and space.

The most commonly used system of musical notation is Western musical notation. It uses a combination of symbols, lines, and dots placed on a musical staff to represent pitch, duration, and other musical parameters. The staff consists of horizontal lines and spaces, representing different pitches from low to high. Notes are represented by oval-shaped symbols placed on the staff, and their placement determines their pitch value.

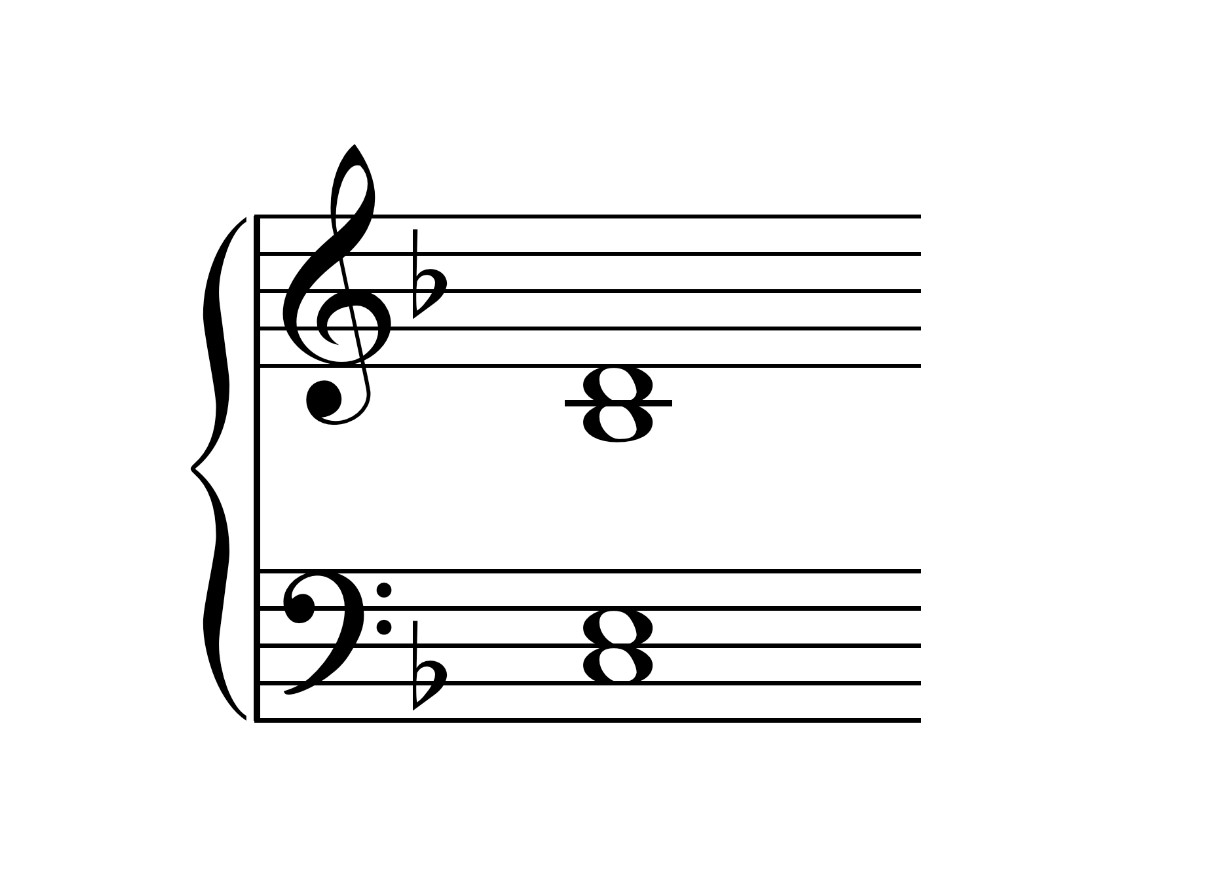

Notation also includes various symbols and markings that convey important musical information. Clefs, such as the treble clef and the bass clef, indicate the range of pitches associated with a particular staff. Key signatures, represented by sharps (#) or flats (b), provide information about the tonal center of a piece. Time signatures indicate the organization of rhythmic beats into measures or bars.

Durations of notes and rests are indicated by the use of different note values. Whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, and their corresponding rests represent different lengths of sound and silence. These durations are further modified by the use of dots, ties, and other symbols to extend or alter their values.

In addition to pitch and rhythm, musical notation includes markings for articulation, dynamics, and expression. Articulation marks, such as staccato and legato, indicate how the notes should be played or sung, whether with short, detached accents or smooth and connected phrasing. Dynamic markings, such as forte (loud) and piano (soft), indicate the relative volume or intensity of the music. Expression markings, such as crescendo or diminuendo, provide guidance on changes in volume or expression over time.

Notation systems have evolved over centuries to meet the needs of composers, performers, and scholars. Early notations used neumes and plainchant to represent melodic patterns in religious music. Guido d’Arezzo’s development of the staff and the use of clefs in the Middle Ages further standardized the process. Over time, additional symbols and conventions were introduced to accommodate the growing complexity of musical compositions.

Today, notation has expanded to include various specialized symbols for extended techniques, microtones, percussion notation, and more. Digital music notation software has also made it easier for musicians to create, edit, and share music notation electronically, revolutionizing the way music is written and distributed.

Notation is a powerful language that enables musicians to accurately convey their musical ideas, helping to bridge the gap between composers and performers. It allows for the preservation and transmission of musical traditions, facilitating the study and analysis of music across cultures and generations. Mastering musical notation is an invaluable skill for musicians, as it provides a universal framework through which musical ideas can be realized and understood.

Key Signatures

Key signatures play a crucial role in music theory, as they provide information about the tonal center and the underlying scale of a musical composition. A key signature is a collection of sharps (#) or flats (b) placed at the beginning of a staff, indicating the notes that are consistently raised or lowered throughout the piece.

The key signature establishes the tonality of a piece and guides the musician in interpreting the correct pitches. It helps to simplify the notation by indicating the accidentals that would otherwise need to be written in front of each affected note. Additionally, the key signature provides insights into the harmonic relationships and the overall mood of the music.

Key signatures are represented by specific patterns of sharps or flats. In a major key, the order of sharps in the key signature follows the sequence of fifths: F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, and B♯. Each sharp added corresponds to a note being raised by a half step. In contrast, the order of flats in the key signature follows the sequence of fourths and is the reverse of the sharps: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, and F♭.

The key signature of a piece is determined by its tonal center or the root note of the scale. For example, a piece in the key of C major has no sharps or flats, as it is considered the natural or neutral key. As the tonal center moves to other scales, such as G major or D major, sharps or flats are added to the key signature accordingly.

It is important to note that key signatures apply to both major and minor scales. While major keys are more commonly used, minor keys also have their own distinct key signatures. The natural minor scale of a key signature follows a pattern of whole steps and half steps, and the necessary sharps or flats are indicated in the key signature.

Transposing music becomes easier with key signatures. When a piece is transposed, the key signature is shifted to match the new tonal center. This allows the music to maintain its structural integrity while being played or performed in a different key.

Understanding key signatures is essential for musicians who wish to read and interpret sheet music accurately, particularly when it comes to scales, chords, and harmonic progressions. It provides a foundation for identifying the tonal center, recognizing patterns in music, and navigating through different sections of a composition.

Whether you are a performer analyzing a classical sonata or a songwriter composing a new piece, being proficient in key signatures allows for greater musical exploration and expression. It enriches your understanding of music theory and enhances your ability to interpret and create harmonically rich and cohesive compositions.

Scales and Modes

Scales are fundamental building blocks in music theory, providing the foundation for melodies, harmonies, and improvisation. A scale is a collection of pitches arranged in ascending or descending order, creating a framework for musical exploration. Scales are vital in establishing tonality and creating a sense of musical structure.

In Western music, the most commonly used scale is the diatonic scale, which consists of seven distinct notes within an octave. The diatonic major scale is a familiar example, as it forms the basis for many melodies and harmonies in Western music tradition. It follows a specific pattern of whole steps and half steps, resulting in a unique sequence of intervals.

Scales can also be classified based on the number of tones within an octave. For instance, a pentatonic scale consists of five notes, while a chromatic scale consists of all twelve semitones within an octave. Each scale offers its own unique character and mood, providing musicians with a diverse range of tonal possibilities.

Modes are closely related to scales, as they derive from the same set of pitches but emphasize different tonal centers (also known as modes of the major scale). Each mode is constructed by starting on a different degree of the major scale and following the pattern of whole steps and half steps. The most well-known modes are:

- Ionian (Major): This is the standard major scale, starting on the first degree.

- Dorian: This mode starts on the second degree of the major scale and has a minor quality with a raised sixth degree.

- Phrygian: Starting on the third degree, this mode has a minor quality with a lowered second degree.

- Lydian: This mode starts on the fourth degree and features a raised fourth degree, creating a unique and bright sound.

- Mixolydian: Starting on the fifth degree, this mode has a major quality with a lowered seventh degree.

- Aeolian (Natural Minor): This is the standard minor scale, starting on the sixth degree.

- Locrian: Starting on the seventh degree, this mode has a diminished quality with a lowered second and fifth degree.

Understanding scales and modes is essential for musicians as they provide a palette of pitches to draw from, shaping melodies, harmonies, and improvisation. Scales and modes offer a sense of order and cohesion, enabling musicians to explore different tonalities, create tension and resolution, and evoke different emotions within their compositions.

Moreover, scales and modes serve as a basis for developing technical skills on various instruments, such as scales exercises for guitarists or fingerings for wind instrumentalists. These exercises and patterns help musicians familiarize themselves with the finger positions and melodic possibilities within a specific scale or mode.

Whether you are a pianist playing a beautiful melodic passage, a guitarist improvising over a blues progression, or a composer finding inspiration for a new piece, scales and modes provide the tools to unlock limitless musical creativity and expression.

Intervals

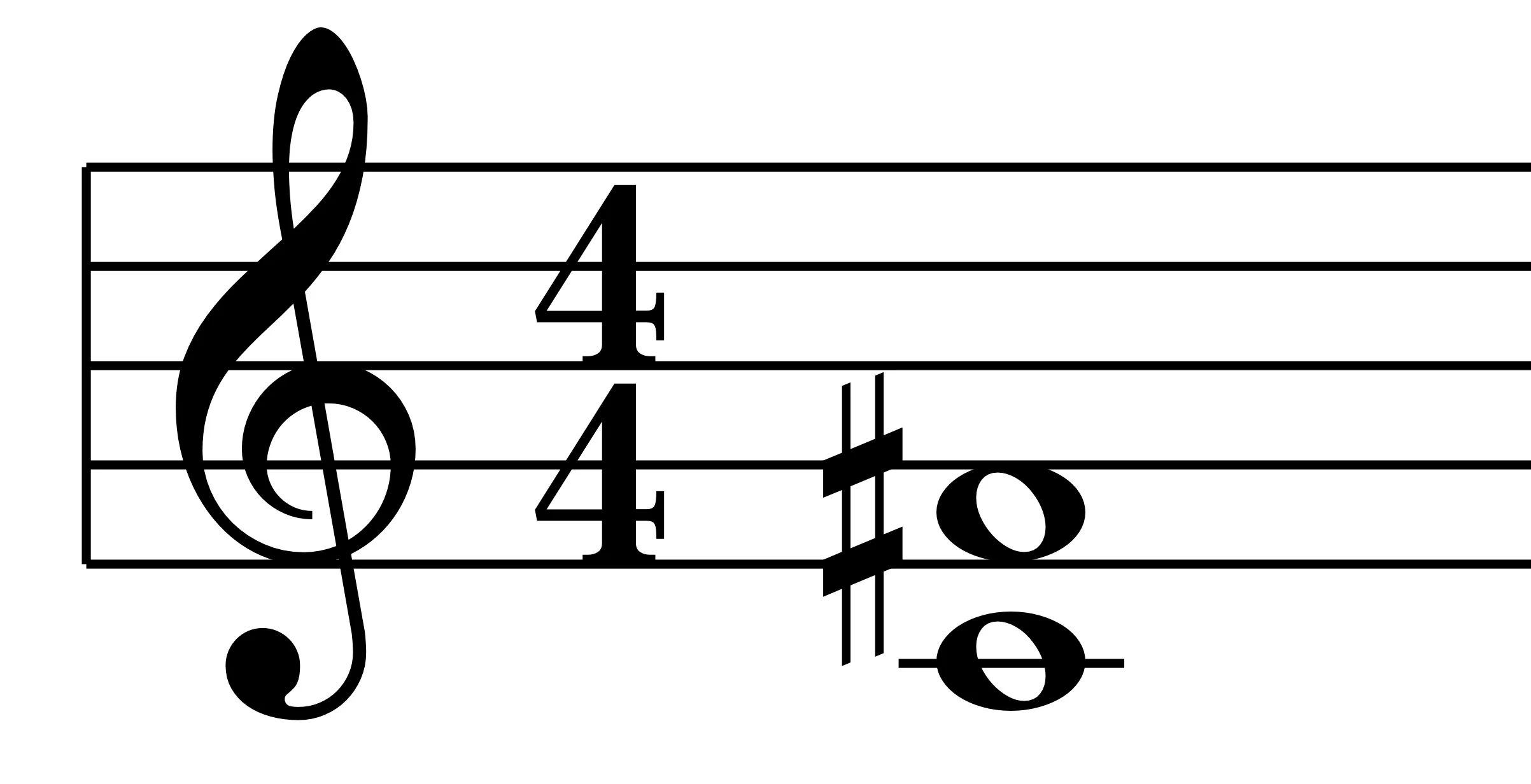

In music theory, an interval is the distance or relationship between two pitches. It provides a way to measure and describe the distance in pitch between two notes, forming the building blocks of melodies, harmonies, and chords. Intervals play a crucial role in understanding and analyzing the relationships between different musical elements.

Intervals are classified based on their size or distance. The smallest interval in Western music is the half step, which is the distance between two adjacent keys on a piano or two consecutive frets on a guitar. A whole step, or whole tone, consists of two half steps. The distances continue to increase, including thirds (both major and minor), fourths, fifths, sixths, sevenths, and octaves.

The quality of an interval further describes its specific sound. For example, a major third has a different tonal quality from a minor third, even though they represent the same physical distance. The quality of an interval depends on the number of half steps it encompasses and is influenced by the scale or key it resides in.

By understanding and recognizing intervals, musicians can identify and recreate melodies, harmonize chords, and transcribe music by ear. Interval recognition is an essential skill for ear training and developing aural proficiency. Musicians can train their ears to distinguish and identify intervals, which aids in transcription, sight-singing, and improvisation.

In addition, intervals play a significant role in chord construction. Chords are formed by stacking intervals on top of one another, creating various harmonies and chord qualities. For example, a major chord is constructed using a major third and a perfect fifth, while a minor chord consists of a minor third and a perfect fifth.

Understanding intervals allows for greater musical expression and versatility. Musicians can incorporate intervals creatively into their compositions, exploring melodic leaps and jumps to add interest and excitement. They can also use intervals to create harmonically rich and complex chord progressions, crafting evocative and expressive harmonies.

Intervals are not limited to Western music. Different cultures and musical traditions may use different tuning systems and intervals outside the standard Western twelve-tone system. Ancient and non-Western musical systems, such as Indian classical music or Indonesian gamelan music, often incorporate microtones and intervals that differ from those found in Western music.

Whether you are a vocalist, instrumentalist, composer, or music enthusiast, understanding intervals unlocks a deeper appreciation of the music you hear and perform. It allows you to navigate the intricate relationships between pitches, create captivating melodies, and build harmonies that resonate with the listener.

Chords

In music theory, a chord is a group of three or more notes played or heard simultaneously, creating harmony and adding depth and texture to a musical composition. Chords serve as the foundation for harmonies, providing a harmonic framework that complements the melody. Understanding chords is essential for musicians seeking to create harmonically rich and expressive musical arrangements.

Chords are constructed by combining different intervals, typically in thirds, within a specific key or tonality. The most basic type of chord is the triad, which consists of three notes: the root, the third, and the fifth. The root is the fundamental note of the chord, and the other notes provide the quality and character of the chord.

Chords can be classified into major, minor, augmented, diminished, and suspended chords, among others. Major chords have a bright and uplifting sound, while minor chords evoke a more somber or melancholic mood. Augmented chords have a tense or suspenseful quality, while diminished chords create a sense of tension or instability.

Extensions can be added to basic triads to create more complex chords. These extensions include the seventh, ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth notes of a scale. For example, a seventh chord adds the seventh note to a triad, resulting in a richer and fuller sound. There are various types of seventh chords, including major, minor, dominant, and half-diminished chords.

Chords are not limited to a specific instrument or style of music. They can be played on piano, guitar, or any other instrument capable of producing multiple notes simultaneously. Chords are used in various genres, including classical, jazz, rock, pop, and blues. They form the harmonic foundation that supports melodies, improvisation, and composition.

Understanding chords allows musicians to analyze and interpret musical compositions, enabling them to identify the underlying chord progressions and harmonic patterns. This knowledge helps in transcribing music, improvising over chord changes, and arranging or composing original pieces.

A thorough understanding of chords also facilitates effective communication among musicians. Chord symbols and notations, such as lead sheets or chord charts, provide a shorthand way of communicating the harmonic structure of a piece. This allows musicians to collaborate, perform, and improvise together more efficiently.

Additionally, chords serve as a starting point for creative exploration. Musicians can experiment with chord inversions, voicings, and substitutions to add their own unique touch or create specific emotions within their compositions and performances. Chord progressions can be altered or reharmonized to generate fresh and inventive arrangements.

Chords are the backbone of harmonies and the essential building blocks of music. By understanding how chords are constructed, their qualities, and their impact on harmony, musicians can create captivating and expressive musical experiences that resonate with listeners.

Cadences

In music theory, a cadence is a melodic or harmonic progression that marks the end of a musical phrase, section, or composition. Cadences provide a sense of resolution, closure, and finality to a passage, guiding the listener’s ear and providing a musical punctuation mark. Understanding cadences is essential for composers, performers, and listeners alike in grasping the structural and emotional flow of a piece of music.

There are several types of cadences, each with its own characteristic sound and function:

- Authentic Cadence: Also known as a perfect cadence, an authentic cadence consists of a V (dominant) chord resolving to a I (tonic) chord. It is considered the strongest and most conclusive type of cadence, providing a sense of resolution and stability. Authentic cadences are commonly found at the end of musical phrases or sections.

- Plagal Cadence: Plagal cadences, often referred to as the “Amen” cadence, involve a IV (subdominant) chord resolving to a I (tonic) chord. These cadences have a peaceful and harmonious quality, frequently appearing in religious and hymnal music.

- Half Cadence: A half cadence occurs when a musical phrase or section ends on a V (dominant) chord without resolving to the I (tonic) chord. Half cadences create a sense of temporary pause or suspension, leaving the listener with a feeling of anticipation or incompleteness.

- Deceptive Cadence: Also known as an interrupted cadence, a deceptive cadence involves a V (dominant) chord unexpectedly resolving to a chord other than the expected I (tonic) chord. Deceptive cadences provide a surprising and unresolved twist, often used to create musical tension or to lead into a new section or modulation.

Cadences can occur within a smaller musical unit, such as a phrase or a verse, or can mark the end of a larger section or movement. They can be used to reinforce tonality, establish a sense of key, or guide the overall structure of a composition.

Understanding cadences helps musicians analyze and interpret music. By recognizing and identifying different cadences, musicians can anticipate musical resolutions, make informed decisions about interpretation, and develop strategies for creating effective musical phrases and sections.

Cadences also play a significant role in musical expression. Composers can utilize cadences to evoke specific moods or emotions. Choosing a particular cadence can imbue a composition with a sense of triumph, tranquility, tension, or surprise, enhancing the overall artistic impact.

Cadences are not limited to Western classical music. Various musical traditions and genres have their own unique cadential patterns and harmonic conventions. Traditional music from different cultures, jazz, blues, and popular music all employ cadences to create musical closure and establish rhythmic and harmonic expectations.

Whether you’re a composer, performer, or avid listener, understanding cadences enhances your ability to appreciate and engage with music. It allows you to recognize the melodic and harmonic structures that give shape and meaning to musical phrases, guiding you through a satisfying journey of tension and release.

Transposition

In music theory, transposition refers to the process of shifting a musical passage, melody, or entire composition to a different pitch level while maintaining the relationship between the notes. Transposition allows musicians to play or perform a piece in a different key, providing flexibility and versatility in adapting music to different instruments, vocal ranges, or personal preference.

The act of transposing involves raising or lowering all the pitches in a composition by the same interval. This interval can be a whole step, half step, or any other distance. When transposing, the overall structure, intervals, and relationships between the notes remain the same, only the pitch level changes.

Transposition is a common practice in various musical contexts. Here are a few situations where transposition is frequently used:

- Instrumental Adaptation: Different musical instruments have different pitch ranges. Transposing music allows musicians to adapt a score written for one instrument to another, ensuring that the music lies within playable range. For example, a piece written for the piano can be transposed to accommodate a saxophone or a guitar.

- Vocal Range Adjustment: Transposing is often employed in vocal music to suit the range and comfort of a particular singer. By transposing a song to a higher or lower key, the singer can perform the piece without straining their voice, allowing for better vocal control and expression.

- Composition and Arrangement: Composers and arrangers frequently transpose their compositions to create different versions or adapt music to specific instruments or ensembles. Transposing can help maintain the desired musical intervals, harmonies, and melodic relationships, while accommodating the needs and capabilities of the performers.

- Accommodating Singers or Specific Instrumentalists: In a collaborative setting, transposing music might be necessary to accommodate the specific range, tonal qualities, or preferences of a particular singer or instrumentalist. Transposing ensures that the music is accessible and suited to the performer’s abilities.

Transposition has significant practical and creative implications for musicians. It allows them to work with the same musical material in different keys, exploring different tonalities and colors. Transposing can also yield artistic and expressive benefits, as different keys evoke distinct emotional qualities and can affect the overall character of a piece.

While transposition is often done manually using music notation or instruments, technological advancements have made the process more accessible. Music software and digital audio workstations allow musicians to transpose music with a few clicks, making it easier to experiment with different keys and explore the possibilities of transposition.

Transposition is a valuable skill for musicians, enabling them to adapt, customize, and explore music in various contexts. Whether in performance, composition, or arrangement, the ability to transpose extends the musical possibilities and ensures that music can be tailored to suit specific needs and artistic visions.

Musical Analysis

Musical analysis refers to the process of studying and examining a piece of music to understand its structure, style, and expressive qualities. It involves breaking down the various elements of a composition and exploring their relationships, patterns, and functions. Musical analysis provides deeper insights into the composer’s intentions, the underlying techniques, and the overall impact of the music.

There are several approaches to musical analysis, each focusing on different aspects of the music. Here are a few commonly used methods:

- Formal Analysis: Formal analysis involves examining the overall structure and organization of a piece. It explores the arrangement of musical sections, the use of phrasing, repetition, and contrast, as well as the development of themes or motifs. Formal analysis enables listeners to follow the narrative, identify musical ideas, and understand the structural framework of a composition.

- Harmonic Analysis: Harmonic analysis explores the harmonic language and progression within a piece of music. It involves identifying chords, chord progressions, and the harmonic rhythm. Harmonic analysis reveals the tonal relationships, tension, and release, and can uncover the expressive qualities of a composition.

- Melodic Analysis: Melodic analysis focuses on the melodic material within a composition. It examines the contour, shape, and development of melodies, identifying motifs, sequences, and variations. Melodic analysis provides insights into the expressive qualities, melodic structure, and melodic relationships in a piece.

- Rhythmic Analysis: Rhythmic analysis explores the rhythmic patterns, meter, and pulse within a composition. It examines the use of rhythmic motifs, syncopation, and rhythmic relationships between instruments or voices. Rhythmic analysis helps to understand the rhythmic complexity, drive, and energy of a piece.

- Expressive Analysis: Expressive analysis goes beyond the surface elements and focuses on the emotional impact and artistic interpretation of the music. It considers dynamics, articulation, phrasing, tempo choices, and other expressive markings. Expressive analysis helps to understand the composer’s intentions and provides insights into the performer’s interpretation.

Musical analysis enhances our appreciation and understanding of a composition. It allows us to delve into the intricacies and intentions of the composer, revealing the craftsmanship, innovation, and artistry behind the music.

Various tools and techniques are employed in musical analysis, including score study, listening closely to recordings, and applying theoretical concepts. Music theorists, musicologists, performers, and educators engage in musical analysis to develop a comprehensive understanding of a piece and to communicate its intricacies to others.

Furthermore, musical analysis can guide performers in their interpretation, aiding them in making informed decisions about dynamics, phrasing, and expressive choices. It informs the performer’s understanding of the overall structure and highlights the significant moments within a composition.

Musical analysis is a valuable tool for both musicians and listeners, offering a deeper understanding and appreciation of the music we encounter. It provides a new lens through which we can explore the intricacies, craftsmanship, and emotional depth of a piece, enriching our musical experiences.

Conclusion

Music theory is a vast and fascinating field that deepens our understanding and appreciation of music. It provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing, interpreting, and creating music. From the fundamental concepts of pitch, melody, harmony, rhythm, and form, to more nuanced topics like notation, key signatures, scales, intervals, chords, cadences, transposition, and musical analysis, music theory unlocks the mysteries of how music works and how it elicits emotional responses within us.

By delving into music theory, musicians gain the ability to communicate effectively and collaborate with others through a standardized musical language. Composers can craft intricate and cohesive compositions, while performers can interpret and convey the expressive qualities of the music. Understanding music theory also enables listeners to engage more deeply with the music they love, recognizing the structural elements, appreciating the composer’s intent, and experiencing the emotional journey crafted within the composition.

Moreover, music theory is not confined to a specific genre or time period. It applies to classical, jazz, pop, rock, folk, and traditional music from various cultures. By exploring music theory, we can uncover the connections and patterns that underlie different musical styles, broadening our musical horizons and fostering a more inclusive and holistic view of music as a whole.

As musicians, educators, and enthusiasts, incorporating music theory into our practice and study enhances our skills, ignites our creativity, and deepens our passion for music. It allows us to explore the intricacies of musical structures, appreciate the artistry of composers, and connect with the universal language of music.

So, whether you’re a beginner starting your musical journey, an experienced musician seeking to expand your knowledge, or simply someone who appreciates the beauty of music, diving into the world of music theory will unlock new dimensions, enrich your musical experiences, and open doors to a greater understanding of the incredible power and artistry that music holds.